By Roni Jo Draper

My father was born and raised in the Yurok village of Weitpus, in what is now considered Northern California. There at the fork of the Klamath and Trinity Rivers, he fished, gathered acorns with his gram, and put fire on the ground so she would have the material she needed for her baskets. Aawok Lucinda, my great grandmother, was a master basket weaver. As a child I listened to my father tell me stories of her baskets and we visited them when they were on display at the California Academy of Sciences at the Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. I took my children on a similar tour and told similar stories.

I never met my great-grandmother — she left this world just as I entered. Sometimes I try to imagine her life on the river, gathering hazel and willow, and spending her days weaving and visiting (no doubt laughing) with her sister. Aawok Lucinda saw all her children taken to the Sherman Indian Boarding School in Riverside, California. They all, thankfully, returned — carrying trauma with them. Like many Native people swept up in the shameful legacy of boarding schools, my grandmother and her siblings did not talk about their experiences at Sherman. But their lives revealed evidence of their ability to survive in a world that explicitly tried to erase them.

I wish I could ask Aawok Lucinda about the experience of watching her children leave and return. I would like to know how she dealt with the sorrow of their absence and the joy of their return. I would also like to know about Aawok Norma’s experiences. I would like to understand what she faced, so I could bear witness to her suffering and her strength. I can bear witness to her survival and the way that she managed to cope and bring my father and his beautiful siblings into the world. I cannot say that she thrived in this world, but I know she loved mightily and laughed boldly — traits I endeavor to carry well today.

I thought a lot about Aawok Lucinda and Aawok Norma while I watched Paige Bethmann’s Remaining Native. It is a beautiful story about Ku Stevens, a young Paiute man from Yerington, Nevada, with dreams of running for the University of Oregon as part of the famed Ducks track program. Growing up in rural Nevada with little access to coaching and competition, makes his dreams virtually untenable.

Remaining Native is also the story of Ku’s great-grandfather, Frank Quinn, who ran away twice from the Stewart Indian Boarding School in Nevada as a very young boy. Like many Native Americans of Turtle Island, Ku finds himself between life on the reservation — in his case in Yerington, Nevada — and dreams that seem too many miles away. A runner, Ku can’t help but reflect on how his running through the desert landscape of the Great Basin is similar, yet vastly different from his great-grandfather’s experience of running on the same land.

My grandmother, Aawok Norma, married a Filipino man. He was not the father of my father, but he fathered him, nonetheless. The recipe I’m sharing is a variation of his. When he came to visit, he always made us chicken adobo. It is a simple and versatile dish, and it reminds me of home, family, and comfort. I make it for my family now in a crock pot in keeping with the Native way of doing traditional things using new technologies. Ha.

Crock Pot Chicken Adobo

1 package of chicken (6) thighs and/or drumsticks. Bone-in and skin-on are preferable for the best flavor, but I have been known to use boneless, skinless thighs with great success.

¾ cup vinegar. Any vinegar will do. I generally use white vinegar or apple cider vinegar.

½ cup soy sauce. I use Kikkoman’s dark soy sauce.

1 can of chicken broth. I use low sodium because of the soy sauce. But if you don’t have chicken broth or bouillon you can use a couple of cups of water.

3 gloves of garlic. That is just a number I wrote here — measure with your heart. I don’t think you can use too much garlic.

2 shallots coarsely chopped. Again, I don’t get too picky about the onion — use what you have got.

3 bay leaves. I know that it can feel like bay leaves don’t do anything, but trust me, this dish needs the bay leaves.

1 tablespoon of black peppercorns. I used to put these into the pot to float freely around during cooking, but they are hard to pick out afterwards and my family doesn’t enjoy biting down on whole pepper corns. So now I place them in a tea steeper and put them in the pot. The dish gets all the flavor of the pepper and it is easy to remove them before serving.

2 tablespoons of sugar. This can be either regular granulated sugar or brown sugar. If you are concerned about the added carbs, not much is lost by leaving it out.

Place all the ingredients in a crock pot and cook on high for about two-and-a-half hours. Serve over white rice. I usually just dip out the brothy goodness as is, but I have also been known to transfer the broth to a saucepan (after straining it) and mix in a little cornstarch/water slurry over medium heat to thicken it a bit.

The last time I made adobo for my family, my eldest son put some broth in a mug and drank it. He mentioned that when he is sick, he wants adobo broth to comfort him and help him heal. This memory floats through my mind as I consider Ku’s experience. Upon hearing of the bodies of children buried at the Stewart Indian School, Ku decides to commemorate his great-grandfather’s run by running the 50 miles from Yerington to Stewart. Ku organizes a run over two days across the Nevada desert, and, well, you must see the movie. What I will say is that watching Ku’s efforts healed something inside me and comforted my soul.

I felt a hope in Ku’s relationship with his family and with the land. That hope rested easy beside my own longing for reconciliation and the possibility that my ancestral matriarchs are knowing peace on their journeys. And I suppose that is how it is with Native stories, and young people who have space to thrive, and dreams.

Wok-hlew

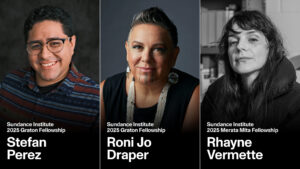

2025 Graton fellow Roni Jo Draper, Ph.D., is an enrolled member of the Yurok tribe and a writer-director. Roni produced Scenes from the Glittering World, stories of three Diné adolescents living on the fringes of the Navajo Nation. She also produced, directed, and wrote Fire Tender, a short film highlighting the work of Margo Robbins and Yurok cultural fire practices. Roni’s work has been supported by the National Geographic Society, Vision Maker Media, and Women Make Movies.