By Jessica Herndon

Lauren Greenfield has always had an eye for America’s obsessions. For over two decades, the Emmy Award–winning filmmaker has focused her lens on the most uncomfortable truths about wealth, beauty, and youth culture — from the devastating intimacy of Thin (2006 Sundance Film Festival) to the gaudy excess of The Queen of Versailles (2012 Sundance Film Festival; winner of the Directing Award: U.S. Documentary).

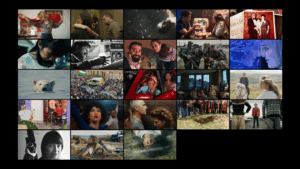

Her latest documentary series, Social Studies, which premiered at the 2024 Telluride Film Festival and is now streaming on Hulu and Disney+, earned her another Emmy nomination for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series. This time, she’s dissecting the generation that grew up with smartphones glued to their palms.

Social Studies is an ambitious social experiment: a year-long deep dive into the lives of Los Angeles teenagers who’ve never known a world without Instagram and TikTok. Greenfield didn’t just film them — she gained access to their social media accounts, spending nearly two years organizing live footage and 2,000 hours of screen recordings to capture both their IRL and digital moments. The result is an unfiltered look at adolescence in an age where your worth is measured in likes.

Greenfield, who has been documenting youth culture since her 1997 book, Fast Forward, which explored L.A. kids obsessed with the celebrity lifestyle, has become increasingly fascinated with how young people growing up in the digital era are “losing their innocence in a media-saturated society,” she says. For Social Studies, she didn’t choose just any teenagers. Most spent their freshman year locked down during COVID, making their phones even more central to their identities.

During a candid Sundance Collab event titled Spotlight: Documenting Digital Lives with Lauren Greenfield (Social Studies), the filmmaker reveals how she gained the trust of the teens — and their parents — who appear in her series, how she identified the show’s themes, and creating the visual language of the show.

How she gained the trust of the teenagers in her film.

I’m very transparent about the process. And the world that we live in today is different from when I started this work. People Google you and know everything about you before you even show up at their door. So, that actually helped a lot with the young people and with some of their parents — they could look at [my 2002 book] Girl Culture and understand my creative point of view.

But also the subject matter — we were looking at social media [and] we were going to take a critical, deconstructing look at it. It was going to be honest. It wasn’t going to be fake or reality TV. There wasn’t going to be approvals. This was actually a kind of social experiment where it needed to be real.

Also, people are coming back from COVID. This is the beginning. Everybody was so isolated, dealing with things on their own, and there was something appealing about being together in this group.

How she pinpointed which topics to focus on in the series, which explores bullying, body insecurity, anxiety, racism, and more.

A lot of the kids felt like they had stories to tell, and they wanted to tell them if they could trust the storyteller. And they also had skin in the game — concerned about the issue or invested in the issue, though people came to it from different perspectives.

Sydney had been slut shamed, and she decided this was the place she was going to talk about it. She actually hadn’t even told her parents all the details of the story, but she decided to do it here. And [the kids] weren’t just subjects, they were also my co-investigators, my co-creators. That was exciting. I really needed them to tell me what were the important issues and then lead me down following them in their own lives. But it was a strange and different role that they had compared to my other documentaries, because they were both subjects and they were experts. That was really key to my approach. I didn’t want to have talking head experts, academics, tech companies. I really wanted it to come from the kids, but to come from the kids in a personal way.

On how she homed in on the visual approach for the series.

I really always wanted to have social media embedded in the live action. I didn’t want to cut to black and see a screen. I wanted to have it live on top of our frame. And so that was something that I worked on with an animator. Early on, when we were doing a proof of concept reel where we filmed with kids and captured social media, we started to figure out how this would all be possible. And one of the things that I had to get everybody used to was, we need some space for the screen. So, all the DPs had to put aside their normal, beautiful rules of composition and give me negative space so I could show what was going on.

I also wanted to incorporate the aesthetics of the language. I didn’t want to make it too much about a certain brand or a certain platform. But I also didn’t want to devoid it of the way we normally see it. I thought aesthetically, the media is the message. We need to see the way it comes in. We need to see the speed at which people are ingesting it. We need to see [someone] going from one thing to another: You’re in school. You’re listening. You’re taking notes in school, but you’re also playing a game. You’re talking to your boyfriend, but then your mom interrupts, and you’re also talking to her.

Technically, it took me a while to figure out how to do it. My son, who was 14, ended up figuring out a hack for me to get into one of the program’s live feeds. And then I worked with this amazing animator, Eric Jordan, who was out of New Zealand, and he helped me figure out the the visual language of adapting the actual real screen recordings and data into a screen interface where we could have it be legible fast enough to simulate real social media, but slow enough that a viewer could read it and understand it.

On how she was able to capture and organize 2,000 hours of screen recordings.

We had one person who was dedicated on set to capturing the phones. We could not wait too long [to capture screen recordings] because the kids are using their own phones, and they might not have that much memory. We had to take it off in intervals. We also did a plug-in situation where we could get it live. We organized it by character. We organized it by theme.

On the difficulties of filming teens.

I really try to take on a nonjudgmental approach when I’m filming. I know from my own kids that coming down hard and being like, “No, don’t do this…” I mean, I do that as a mother, but sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. A lot of times, some of the behaviors we were seeing were things they were keeping from their parents, teachers, or therapists, and they already had that authoritarian structure in their lives.

That said, I think we’re all humans first. And if you’re in a situation as a documentarian where you’re the only one who can help and somebody is at risk of getting hurt, you have to take care of that first.

And as hard as keeping up with social media technically was, it’s really hard to keep up with teenagers. They are super flaky. We got this whole crew that costs money, and we’ve got teenagers that don’t have any sense of that, and we don’t want them to be thinking about that either. But, you know, Keyshawn, for example, so many times, would stand us up. We’d be all ready to do something, and then he’d be like, “Oh, no, no, no. I’m doing something else.” That would happen all the time. Those were the harder things in terms of finance and planning.

On whether she thinks filming on a smartphone will overtake the use of digital cameras in documentary filmmaking.

No, I don’t. I love the big camera. I come from photography. I love quality. I do think maybe I’m too obsessed with quality in the sense that I think I probably could have loosened up and shot myself more with a phone. But I think that one of the things that I really like in the show is the different visual languages contrasting with each other.

Our camera is a big, beautiful camera — that’s what I’m seeing. The subject’s camera is the phone, and that vertical is a different quality. I don’t think it [will] replace the big, beautiful camera. What you can do with the phone is not as good as what you can do with the big cameras.