By Alexis Neophytides

For Jay and me, filmmaking wasn’t just a response to crisis, it was a way through it.

I first met Jay in the summer of 2019. He was living in Coler Rehabilitation and Nursing Care Center on Roosevelt Island — the same island where I grew up. A mutual friend introduced us because Jay had just won a grant to work with a professional filmmaker. She knew I’d been teaching documentary filmmaking and that I loved the island and its community. She thought we’d hit it off and she was right.

Jay’s journey into filmmaking had started a few years earlier. In 2014 he developed a rare lung disease that left him paralysed with a weakened heart, lungs, and kidneys. After a long stay in another care facility, he was transferred to Coler, where he met a group of residents — mostly young men living with spinal cord injuries from gun violence. There wasn’t much for them to do there because most of the nursing home’s activities were geared towards the older residents.

A neighborhood artist who knew the men started a writing workshop called OPEN DOORS, inviting mentors and bringing in resources. The group began writing poetry and eventually called themselves the Reality Poets. They started performing at schools and community spaces across New York City, sharing their stories to challenge assumptions about disability and build community.

Jay said the poetry woke up their creative sides. Members of the group branched out into music, design, theater, and, for him, film. By the time we met, Jay had already spent countless hours teaching himself filmmaking: watching YouTube tutorials on Premiere and After Effects, experimenting, figuring things out on his own, and making short films. He had a fire in him to learn and to create and refused to let his circumstances define what was possible.

When the pandemic hit in March 2020 and Coler went into lockdown, I was terrified for Jay and the rest of the group. Not long after, the nursing home moved a Covid-positive patient into his room. Jay was furious and scared. He said, “We need to tell the world what’s happening in here.” That was the beginning of Fire Through Dry Grass.

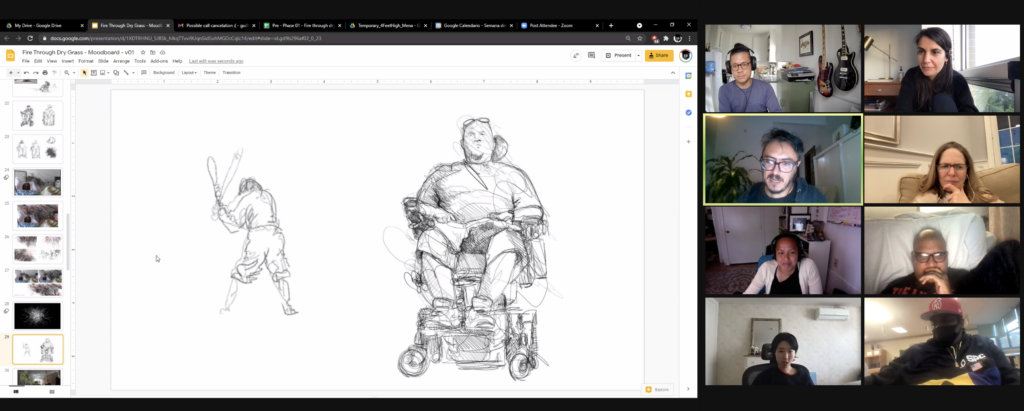

He and the Reality Poets started filming inside, using cellphones and GoPros clamped to their wheelchairs. I filmed from the outside. We recorded countless Zoom meetings.

At first, we thought we were making a short film — something quick to sound the alarm — but the situation kept getting worse. And as it did, our circle widened. The Roosevelt Island community rose up, forming a Coler task force, organizing meetings with elected officials, and helping to plan protests. Then support began to arrive from the wider filmmaking world. We received our first small grant, which gave us the courage to keep going. Our incredible executive producers (Sara Bolder and Jim LeBrecht) came on board, bringing their advocacy and belief in the film’s resonance within the larger disability community. We received both financial and in-kind support from teams of lawyers to mentors across the documentary field, including Sundance Institute, whose creative guidance helped us shape the film into its final form.

In our own collaboration, Jay’s and my creative sensibilities couldn’t have been more different. I am drawn to quiet, observational moments; Jay loved spectacle, big special effects, and drama. He challenged me to loosen my ideas of what I thought a documentary had to be or look like, and the film found its rhythm in the tension and space between us.

Jay’s dual role as director/subject pushed me to think about all the other protagonists’ roles in the filmmaking process. We got on board with the spirit of collaboration and making community art that was already the ethos behind OPEN DOORS. The other Poets took on roles collaborating with outside artists: working on the score, graphic elements, writing, and watching cut after cut to give feedback.

As Jay and I made the film, our work and our friendship became inseparable. Through the Zoom box we had a direct window into each other’s worlds. We were confidants. There were many deep conversations — some bits making their way into our film — about loss, love, and what it means to keep going. We also talked endlessly about the trivial things that made life bearable: the latest Game of Thrones plot twists, what to eat for dinner, what his next LEGO set should be.

Jay loved superhero movies — the big, loud, CGI ones — and he talked about them with the kind of seriousness other people reserve for philosophy. I know he saw something of himself in those stories — people shaped by pain who still choose to fight for others. In one of his poems he wrote:

Some superheroes are born with special abilities,

Few are turned by tragic events.

Others are shaped by possibilities,

But we were turned into heroes by our disabilities.

Together, we made a film about Jay’s most traumatic time, in real time, with the goal of protecting and improving the lives of nursing home residents everywhere. And all the while, his body was deteriorating. He started dialysis and had less energy for work. There began a new kind of balancing act — when to rest, when to push him to do something, how to prioritize his energy for decisions that mattered most in the film.

We finished Fire Through Dry Grass in the summer of 2023 and premiered at BlackStar, where the film won the Jury Award for Best Documentary Feature. That day was unforgettable. Jay called it the best day of his life. All the Reality Poets traveled to Philadelphia for the premiere. We were a crew of 20, filled with pride and disbelief that we’d made it there together. Not long after, Jay told me he could die happy. He was so proud of what he had achieved.

Jay passed away this July.

Fire Through Dry Grass went on to become a The New York Times Critic’s Pick and aired nationally on POV. The film is now being used by long-term care advocates, disability rights activists, and other changemakers to raise awareness, protect nursing home residents, amplify disabled voices, and drive reform across the care system.

Our work together, and our friendship, got us both through a terrible time. It reminds me that in dark times, like the ones we find ourselves in now, making art together is a powerful way to survive.

Jay’s full poem:

Some superheroes are born with special abilities,

Few are turned by tragic events

Others are shaped by possibilities

But we were turned into heroes by our disabilities.

Our desire to overcome our failures,

Ended up turning us into our own saviors

And then we realized we were able,

To be who we wanted to be without being labeled.

After hitting rock bottom and almost dying

We understood it was get rich or die trying

But rich with knowledge instead of rich with money

Rich with desire to help other people

Telling them about the mistakes we made

That led to us being cripple,

We have come so far since our tragedies

Far from being just one of many casualties

We put on a cape and a cowl

Just like the DC hero the night owl

We have shown others that this wheelchair it’s not the end

That instead it’s the beginning of our new lives

Lives that now have a meaning

Lives that are sincerely willing

To keep working with our youth until our last days

Or until our debt to society it’s finally paid.