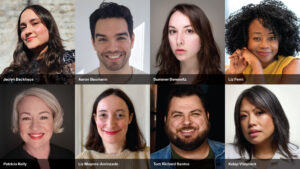

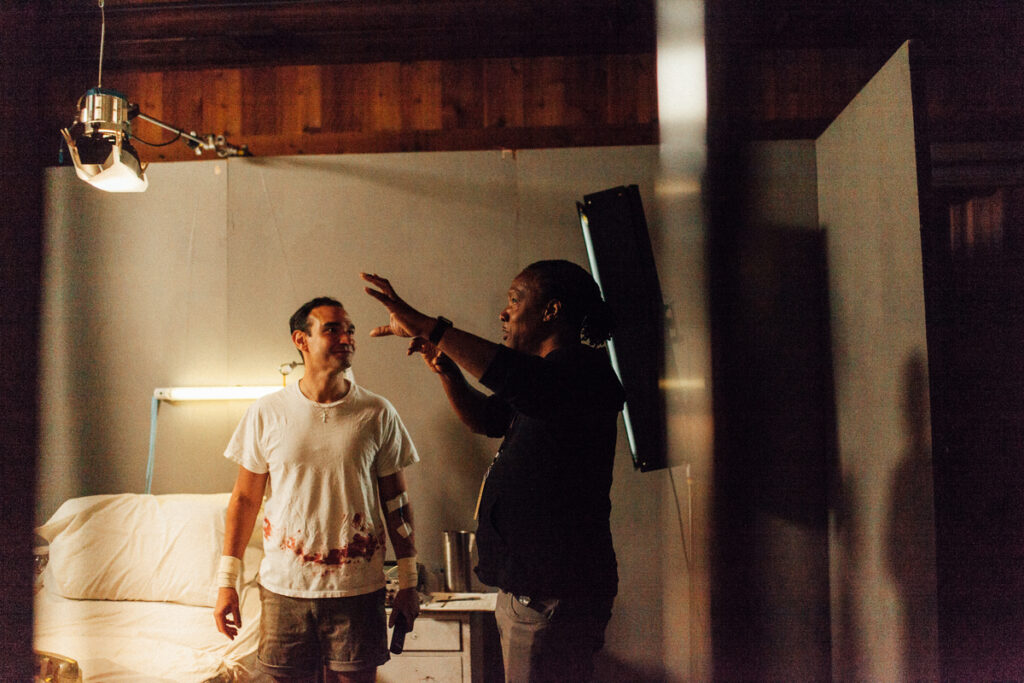

Director Roger Ross Williams on the set of Cassandro during the 2018 Directors Lab. (Photo by Fred Hayes)

By Jessica Herndon

As the Sundance Institute Directors Lab turns 45, we’re celebrating this milestone by highlighting filmmakers who are an integral part of its legacy. Through this special series, we dive deep into the stories of directors who began their narrative feature filmmaking journey at the lab and went on to make an indelible mark on cinema. To ensure future fellows have access to this formative space, we invite you to make a gift and join us as we champion independent voices by keeping the labs alive.

Roger Ross Williams cried a lot at the Directors Lab in 2018. Though he entered the lab as an Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker after becoming the first African American director to take home the Best Documentary Short Film Academy Award for Music by Prudence in 2010, Williams was still just a fellow looking for his voice. “My first couple scenes at the lab were a disaster in my eyes,” he remembers of developing his narrative directorial debut, Cassandro.

The film follows the true-life story of a lucha libre wrestler who broke stereotypes by wrestling in drag. “The material could lend itself to being very campy and over the top, and I was struggling to find the tone of the film. There was that process when you sit with the advisors in the theater at the resort, and you’re watching your scene with them, and it’s a scary moment because you are so vulnerable. The first two screenings I left crying, feeling that I couldn’t do this.” As Williams, who won Best Direction for his documentary Life, Animated at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, throws his hands up as if defeated during our Zoom chat, he adds, “I failed.”

However, when he screened his third scene, an intimate scene, he was emotional for an entirely different reason. Robert Redford was Williams’s creative advisor during the lab, and he’d coached him through getting the best performance out of his actors and establishing the mood of his film.

“He said to me, ‘You don’t have to over-embellish an already over-the-top scene. In a way, it’s like it’s playing it down, taking it down a couple notches with the actors so that it’s much more internal and emotional,’” recalls Williams. “I did that on the sex scene, and I remember when I screened it, Christine Lahti was one of the advisors. She started to cry when the scene ended. And Redford turned to me, and he said, ‘This is a perfect scene.’” Williams lights up as he leans toward his computer, filling the computer screen with his infectious smile as his dreadlocks hang over his left shoulder. “I cried again!” he adds, his honeylike tone rising a few octaves. “That was the greatest moment in the lab for me. I’ll never forget when he said that. Then the next scene I loved. I found the tone of the movie.”

Cassandro, starring Gael García Bernal, premiered at the 2023 Festival to critical acclaim. The movie underlined Williams’s notable flair for marrying personal storytelling with a broader commentary on society and his ability to take on important, often underexplored topics with empathy and authenticity.

Below, Williams details how the lab helped him develop self-assurance as a narrative director, the lesson he learned from Robert Redford about directing actors, and paying it forward among the Sundance Institute community, as a previous program creative advisor and mentor, an alum advisory board member, and a Sundance Film Festival Documentary Competition juror.

You had a storied career as a documentary filmmaker prior to the 2018 Directors Lab, but in what ways did the Directors Lab help build your confidence as a narrative feature director?

The Directors Lab changed everything for me. I guess I had a successful documentary career, but it’s a different language to do a scripted narrative film, and I needed to learn that language in a safe environment where I could make mistakes, I could screw up, I could experiment with my storytelling style and voice — and I was able to do that at the Directors Lab, and it was invaluable. I get emotional when I talk about that experience, because it was really like a religious experience.

How so?

I think because you spend so much time working in a vacuum on your script, and it lives in your head, and getting it out of your head and onto the screen is a traumatic and difficult process sometimes. So, you need to have a place where you can do that, that’s safe. So, for me, and I think for everyone, all the other directors at the lab, we were all in this kind of very vulnerable, emotional place with our work. And we leaned on the brilliance of the advisors, but we also leaned on each other. We were there for each other. You create this camaraderie, and you can be vulnerable in a way that you can’t be vulnerable in the real world. We were leaning on each other emotionally in a way that really allowed us to express how terrified we were of actually having to make these films, and then put them out into the world.

The beautiful thing about the lab and about the beautiful, amazing Michelle Satter is that she is so nurturing in that she allows you to express your deepest vulnerabilities. She allows you to go there and feel safe. It got to a point where I would just see Michelle and start crying.

What you’re explaining sounds so therapeutic.

It’s like part therapy, part religion — the Sundance religion that I worship at the altar of. It is both of those things wrapped into one.

What would you say is the most valuable lesson you took away from the experience?

My most valuable lesson was really to trust my own voice, and also that I had a skillset that I needed to use and tap into. Coming from documentary, I was like, “Well, I don’t know how to talk to actors.” But I realized that I actually had incredible skills because I had been dealing with real people, and these were trained actors. They’re like machines you can calibrate. And it was Bob Redford, who was my advisor. He was with me in rehearsal, he was with me on set, he was with me in the edit, and would come to the edit room. We would have lunch together. He really taught me how to utilize those documentary skills to work with actors.

There was a moment when we were sitting in the cafeteria having lunch, in the mess hall, and I was saying I was about to tackle the sex scene in my film. I was very nervous about that scene because in the lab, Ilyse [McKimmie] and Michelle encourages you to pick scenes that are going to be challenging to you and are difficult for you, so you can work through those. He actually sat with me and drew out the storyboards for the scene. And then, we went to set, and he blocked it out with me. I was like, “Who else in the world can have Bob Redford storyboarding your sex scene and blocking it out with you?” I framed those storyboards with pages of the script, and I have Redford’s hand-drawn storyboards of my sex scene hanging in my office. It’s insane.

Talk about invaluable!

It’s invaluable. It’s amazing, and I think it was one of the last labs that he actually worked with a filmmaker on. I just so value that time with him and how he was so incredibly encouraging, but he also really gave me this really practical — I mean, he’s just like the god of filmmaking. To have that time with him was unbelievably life-altering and life-changing.

Robert Redford helped you find the language to transition from directing docs to directing actors. How did he coach you through that?

So, he said, “What is your goal when you are interviewing a documentary subject?” I was like, “For them to get to a place of honesty and vulnerability.” He’s like, “And how do you do that?” I said, “Well, often I will use myself. If I get to a place of vulnerability and honesty, they will feel safe enough to share that with me.” And he’s like, “Well, that’s the same way you would do with an actor.” I was like, “Really? Oh my God. I never thought about that. I thought it was secret code language.” And I was like, “Well, I can do that. Do you mean I can actually talk to an actor like a person, and talk to them about my own experiences or their experiences to get them to a place that they identify with the material?” Yes.

And we would walk through and roleplay the characters that were in the scene I was shooting, and how I would talk about that to get them there. Then, he would be on set with me, and as I was talking to the actors, he would be in my ear. He’d be literally in my ear and say, “Remember what we talked about at lunch?” He goes, “Try this,” or “Try that,” and I had Bob Redford in my ear on set. I was very lucky.

How did the lab help shape the way you’ve come to view your role as a storyteller within the broader film industry?

The lab gave me confidence that my voice was important, that my point of view was important, and I wasn’t trying to fit into anyone else’s box. After the lab, I held onto that, because if I get a script that I haven’t written, if someone reaches out to me about a piece of work, it has to feel personal to me. I gained this confidence as an artist so that I can trust my own voice, and that I would never settle or compromise on that.

I just cherish that time so much in the lab, that I wish I could do it again, in a sense. I’m like, “I’ll never have that time again. I’ll never have the first movie. I’ll never have that innocence.” I am jealous of people who get to go. I remember walking down in the morning from our house to the first meeting we were doing that day, that magical walk through the mountains, and the mist early in the morning. I loved that morning walk. It was so inspiring and beautiful. And I didn’t talk to an outside person for the entire five weeks. I was just so focused, and you need that focus. You need that time to focus. You don’t get that time in the real world.

The lab is tough and hard, but it’s also inspiring in so many ways. And then you go out and make your movie, and you’re like, “Wow, this is even tougher than the lab.” Thank God I had that, because I thought it was the toughest thing. I thought the lab was the toughest thing I would ever do. I was like, “Oh, wait. No. Actually, making the film is the toughest thing I will ever do.” And I don’t know if I would’ve gotten through it if I didn’t have the lab experience before that. It set me up for walking onto set because you can’t be vulnerable and crying on set as a director. You gotta be sure of yourself because everyone’s looking to you for answers. But in the lab, I was a crying wreck. I cried every day.

You got through it, and you’ve become what Michelle and Robert Redford were for you, for other creatives!

I have a friend doing the Directors Lab, this next lab coming up, and she’s also a documentary filmmaker, and she’s making the jump. I was like, “I’m here for you. I’m here to give you all the support you need. It’s going to be life-changing.” It’s like stepping on hallowed ground, and all the people who’ve come before you come back. It’s a testament to what the lab is about — it changed their lives as artists, so they come back to give back. It’s a beautiful thing.

What advice would you give to up–and–coming filmmakers who are hoping to attend the Directors Lab in the future?

If you’re hoping to attend the Directors Lab in the future, the main advice I would give is to stay true to your artistic voice. What’s unique about the lab is that everyone there had something to say in their own way. They had a unique perspective, a unique voice that was different than the mainstream, that was different than the type of films that we see in Hollywood. They were so unique and so special. If you lean into that, if you lean into that voice, if you lean into that thing you have to say, you can’t go wrong because it’s you and you’re passionate about it, and you are being true to yourself, and that’s absolutely essential. The lab helps you build the confidence you need to stay true to yourself as an artist.