By Jessica Herndon

Producer Anne Carey’s history with the Sundance Institute runs deep. The first film she produced, The Laramie Project, based on the play of the same name, focused on the effects of the 1998 hate crime murder of Matthew Shepard, and premiered at the 2002 Sundance Film Festival. Since then, four of the films she’s produced have been chosen for our labs and 10 of her movies have debuted at the Festival. When Carey was asked to serve as a creative advisor at the 2012 Sundance Institute Feature Film Producers Lab — and again this year — she said yes without hesitation.

“To be invited was really something. I was honored to get that invitation,” Carey remembers of the first time she got the call to be a creative advisor. “I’d had a number of films that had been at the Festival, and I was very interested in the opportunity to give back to the organization that had helped launch films that I had produced.” She pauses, running her fingers through her pixie cut as she chats via Zoom from New York. “That there is a belief that I can contribute to the support of young voices is very appealing to me.”

One of the most incredible aspects of our labs is the experienced advisors our fellows have the opportunity to interact with during the programs. And who could be more suitable to guide the next generation of dynamic storytellers than Carey, whose commitment to authentic stories and consistent willingness to push boundaries make her one of the most respected producers in the industry today.

Committed to working with unique voices, her films often bring perspectives that challenge conventional narratives, which has led her to carve out a distinctive space in the independent film landscape and beyond.

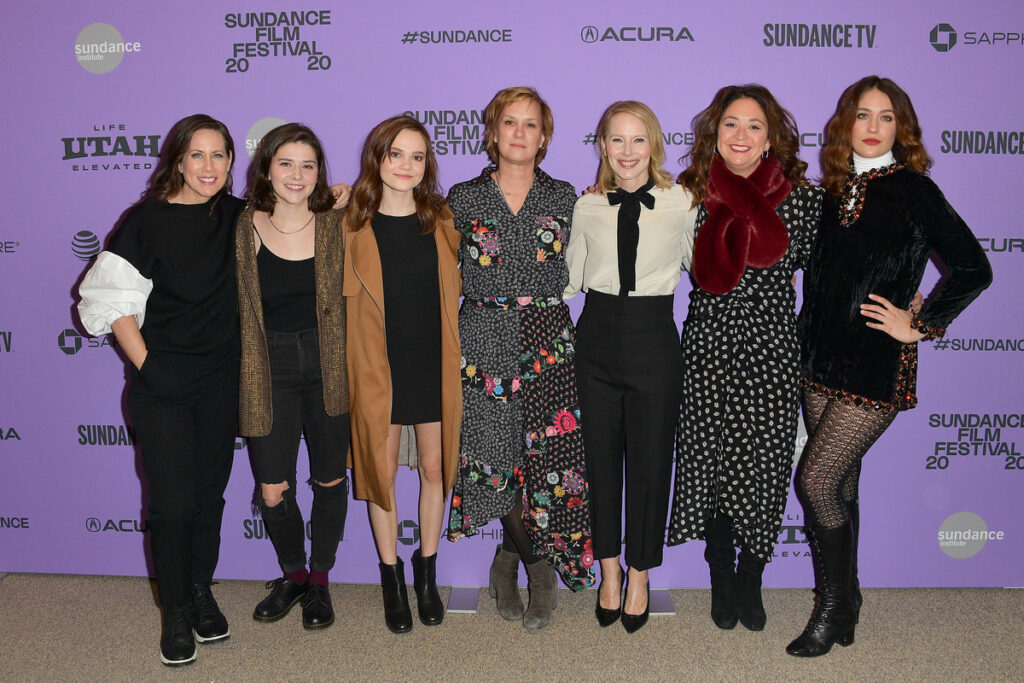

Drawn to films that explore deep, often unspoken aspects of our experiences, Carey’s ability to recognize the infectious complexity in projects like Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl and Nightbitch, Sara Colangelo’s Little Accidents, Liz Garbus’s Lost Girls, Anton Corbijn’s The American, and Nicole Holofcener’s Friends with Money, highlights her unapologetic grasp of storytelling.

As we continue to explore the impact of creative advisors at the Institute over the years, we spoke with Carey about the best advice she’s given to producers over the years, which stories catch her eye, and how the labs set the tone for success in the film industry.

How would you describe your style as an advisor?

I like to think that I’m generous. I definitely feel that I can be rigorous. I definitely intend to mentor a filmmaker to find the best version of their film, not find the version of their film I think they should make. That’s not the job of a producer, and it’s certainly not the job of an advisor at the Sundance Institute. So, I think [the lab] is about, for me, it’s a question. Well, it might be through a series of questions about intention, tone, theme, character, and why you’re the right filmmaker for this story. When I’m developing scripts as a producer, and I think when I’m mentoring or looking at anybody’s script, it’s a question of: This is how I’m responding to your material. Was this your intention? So, it’s about intentionality. It’s about constantly returning to similar questions and starting with very big picture questions.

And once the big picture questions are answered, the specificity comes in. I don’t think you can start asking super, super specific questions until you’ve asked the big questions. It’d be like putting furniture in the house before you built the house. Right? So, what’s the house look like? And then what’s in the house? The rigor comes from being able to say, I’m not understanding this, or I’m not getting this, or Is this what you intended? It should be a series of hopefully being supportive.

What kind of projects and ideas really tend to stand out for you?

When you feel that everybody [involved in a project is] making the same ambitious movie that’s very individually voiced. Of the movies that we have, they’re all very specific to the filmmakers involved — the producers, writers, and the writer-directors — so there’s a good, strong, solid team that is ready to do the work. They have to understand it’s going to change along the way, but it won’t get knocked off its axis. It’s got a strong enough access that it can be interrogated and come out better.

How do you help producers navigate the challenges between maintaining the creative vision and what the practical realities are of filmmaking?

It goes back to the process of just being really clear about what movie everybody’s trying to make. And a lot of it comes from experience, about saying, “I didn’t have this exact situation, but maybe I’ve seen a similar situation happen.” And trying to get a sense of where people feel they’re strong and where they think they may not be strong. And trying to understand the budget, content, and audience — what are the key things to hold onto? And if you have to let things go, because inevitably you will [while] making a movie — you’ll never get everything that you want — what are the essentials? You have to be able to identify your essentials, because those are the things that you’ll protect.

If you can hold onto those essentials, then things that might feel — well, we probably won’t get the boat, the plane, and the train to convey that the character got from point A to point B. So, what’s the essential one? Or you might think that you’re going to absolutely need the Rolling Stones in your movie, but there’s a really good chance you’re not going to get the Rolling Stones song in your movie. So, what’s that song doing, in case you don’t get the Rolling Stones song? What does the song mean? So, identifying the essentials and then identifying how to protect them is a big part of the process of filmmaking. I don’t know anybody who gets everything that they want.

What advice have you found yourself giving to filmmakers in the lab, regardless of the specific project?

Make sure the producer, the director, or the writer-director are all making the same movie. I would say that’s a really important thing — that everybody really understands what the movie is, because I have been involved as a producer and I have seen movies come apart because that wasn’t the case. And make sure that every partner or every person that you bring onto the movie is making the same movie that you’re doing. So, pick your partners carefully.

Sometimes, in desperation to get a movie made, people might take on partners who don’t have the same goals or ethos. So, it’s really important to make sure that you’re putting together a team of people that are going to be really good collaborators and make sure everybody has the same intentions and the same outcome. That’s a really big piece of advice. And I think the other thing is, every person who comes to the movie, whether it’s an actor or a financier or a location scout or anybody, anybody who comes to your movie to make your movie is coming because they want to be involved in what you’re doing.

The other thing I might say is communicate, communicate, communicate. Make sure you’re talking to everybody all the time and look around and figure out where your assets are. Most first-time independent films get made because there is a circle of people you can almost reach out and touch. Where I’ve seen people get caught up, as a first-time filmmaker, as a first-time filmmaker producer, is thinking, “Well, we need to get big movie star A to be in our movie.” The reality is, big movie star A is probably never going to be in your movie. Who will be in your movie? What’s beautiful is that you are always dreaming of the best thing, but at the same time, you have to be practical about what’s going to happen and remember to strike that right balance.

What qualities do you think help a producer ensure long-term success in the industry?

A little madness, a little flexibility, and just a passion for the work. It is not the worst job in the world. It’s not coal mining. It’s a luxury to be able to produce independent films. Have an informed sense of community. We were all there again [at the Producers Lab], getting together a month ago, and it was the warmth of that community that the Institute helps reinforce. It’s a community business.

I also recently spoke with Marielle Heller, Roger Ross Williams, Nia DaCosta, and Sterlin Harjo about their time as fellows at our Directors Lab. Each one said the lab was essential to their career. As an advisor, what are your thoughts on that?

The lab creates such a safe, creative environment where you learn about being so open, raw, and clear about what you’re trying to do that if the rest of your career is spent trying to recreate the high level of discussion about what movie you’re trying to make, if you take the lessons from the lab and apply them to any other film that you make, you remember what the process should feel like. This is what you should be trying to recreate every time in terms of how you pick your collaborators, how hard you work on interrogating every piece of your story, making sure that you’ve asked all the right questions, making sure that you have honestly admitted what you don’t know, and found an answer because you dared to ask somebody a question. I think that’s what it gives you.

How do you decide what projects to take on?

I have to feel like I can be contributive, that I can be additive in some way. I have to believe that I can really love it even if the world is saying no, because inevitably, you’re going to go through a process when you’re going to have to be defending it and selling it. So, do I have that level of connection to it? Do I know what it means to me? So, when 70 people have said no to me — when actors and financers say no — I can believe that they’ve all been wrong. I need to be able to feel like I can believe that. I can believe that those no’s are just stepping stones on the way to getting a yes. Finding the right partners. Are we going to get along with one another? Do I feel that we can get through hard times together? I try to make sure of that. You’re building a family every time you put a movie crew together.