by Carlos Aguilar

Anyone familiar with Southeast Los Angeles, an area of this metropolitan sprawl seldom registered in mainstream media, can attest that Pacific Boulevard in Huntington Park has for decades served as a commercial epicenter where Latino residents from surrounding cities — Bell, Cudahy, Maywood, South Gate, Lynwood — converge for business and leisure.

Display windows unsubtly embellished with bright-colored quinceañera dresses, retail stores exclusively dedicated to all your cowboy attire needs, an affordable movie theater (there used to be two of them), and taquerias aplenty pave several blocks from Florence Avenue, where El Gallo Giro offers baked goods and traditional Mexican dishes, to Slauson Avenue, where department store Curacao extends dubious lines of credit on appliances.

“La Pacific,” in all its chaotic wonderment, is central to the geography of the queer coming-of-age drama Mosquita y Mari, the debut feature from Chicana writer-director Aurora Guerrero that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2012. A decade on, Guerrero’s affecting tale of adolescent desire and the plights of children of immigrants remains vital.

Fighting back against the sensationalist lens with which outsiders tend to investigate predominately Latino neighborhoods, Guerrero maps the effervescent friendship that develops between two 15-year-old Mexican American high school students: Yolanda (Fenessa Pineda) and Mari (Venecia Troncoso). In the unspoken truthfulness of knowing gazes and timid smiles, her teenaged heroines find the comfort to be themselves together.

The U.S. born daughter of hardworking parents from Mexico, who have instilled in her the belief that a college education offers an escape route from a strenuous future, Yolanda minds her grades. Mari — who came to this country from Xalapa, Mexico, at the age of five and is undocumented — sees no point in studying when her mother can’t make the rent.

Though they first interact in the classroom, it’s on Pacific Blvd. and its surrounding urban hideouts that Mari and Yolanda, or “Mosquita” (Little Fly), as her new pal nicknames her; test the limits of their loyalty and connection. Throughout the evolution of their innocent love, Pacific Blvd. reappears as it’s where Mari has a part-time job handing out flyers to help at home financially and where Yolanda and other classmates hang out after school.

Not far from there, the two girls soon find a fortress of their own, an abandoned car garage where no one can impose their expectations on them. Lounging around unbothered in this kingdom of rusted metal, they speak with urgent sincerity of their yearnings.

Yolanda muses on her parents losing their lust for life and for each other to the grueling demands of working-class adulthood, while Mari longs to see her grandmother’s garden back in Mexico once more. Early on in their secret afternoon rendezvous, the pair emblazon a promise of a forever bond, not on a tree trunk inside a fable-like forest but on a dusty windshield hidden away from the world. Their impulse responds to the heightened emotion that dominates one’s psyche at their age, thus for them it’s a sacred gesture.

Guerrero traces their burgeoning and unnamed feelings with a lyrical visual sensibility, not often afforded to Latino tales, and delicate performances that make one believe the girls were plucked straight from reality. The production found in Pineda and Troncoso two young performers that approached the emotional landscape of the roles with tenderness.

Beyond the possible recognition of their sexual curiosity, the teenage experience of Yolanda and Mari is unique in that their parents’ circumstances as immigrants profoundly affect their identities. They are expected to honor their sacrifices and fulfill roles that encapsulate the family’s hopes and dreams for a more prosperous life ahead. Their lives are not entirely their own, but in freely deciding to stick together for better or worse they regain autonomy.

These poignant and thematically rich dramatic layers respond to Guerrero’s personal connection to the people in these communities. Her interest is in them as individuals with sorrows and joys worth making cinema about, and not as headlines ridden with biases.

Everyone that surrounds the protagonists in this fiction belongs to the same community. No outside saviors or influences taint the director’s vision for a story centering her own. Notably, Guerrero first intended to shoot the project in the Mission District of San Francisco, but when those plans shifted, Huntington Park emerged as akin substitute.

In praising Guerrero for her narrative aptitude, one can’t forget to applaud the organic sound of the Spanglish dialogue. Yolanda and Mari’s lines glide through both languages without the stilted forcefulness that has been a telltale sign of inauthentic onscreen presentations of Latino communities, both in Los Angeles and across the U.S..

Without hyperbole, Guerrero’s frames were the first where I saw these streets that I regularly roamed with friends as an undocumented teen in the mid-2000s — when $20 would get you a bus pass, a movie ticket, and a $5 hearty special from Tacos Mexico — on screen. Walking up and down this boulevard mitigated, if momentarily, the alienation that plagued me. There, surrounded by familiar strangers, the fear of otherness subsided.

Back when Mosquita y Mari premiered in Park City, Utah, I still worked at a fast-food restaurant in Huntington Park with a staff entirely made of immigrants or their children. In those days Hollywood seemed so far away, physically and metaphorically, that to learn a movie had been made mere blocks away from us and, to an extent, about us, seemed like a glitch in the system. In fact, that’s what Guerrero had done. She infiltrated it from within.

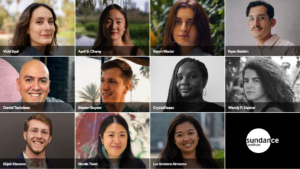

With the support of the Sundance Institute, Latino Public Broadcasting, the Ford Foundation, and allies such as executive producer Moctezuma Esparza — a legend of Chicano cinema behind other landmarks such as Gregory Nava’s Selena — Guerrero scraped together the resources to made real the dream of sharing a story so rarely told.

That a superb storyteller like Guerrero has only recently been able to pursue her sophomore effort, Los Valientes, a decade after this fascinating first outing, only reaffirms what we know about who is afforded repeated support in the industry. Thankfully, Guerrero has found space for her skill set over the last few years in television, helming episodes of notable shows such as Queen Sugar, Gentefied, and 13 Reasons Why.

Though what she accomplished with Mosquita y Mari may not have received the fanfare it merited a few years before the push for diversity and inclusion took over the entertainment business (at least in rhetoric if not always in action), Guerrero made a film almost without precedent and with the artistic maturity of an auteur of the highest order — even if people like her, like Yolanda, like Mari, are hardly ever seen in that light of grandeur.

Serendipitously, the film was released theatrically soon after the Obama administration announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program benefiting undocumented immigrants brought here as kids, myself and Mari included, who were now able to obtain a work permit and a semblance of tranquility in their adoptive home.

And while Guerrero makes no false promises on what her characters’ destinies will become after we last see them, I’d like to imagine that Mari qualified for DACA and that this temporary reprise from the threat of deportation and new opportunities for employment enabled her to see other paths forward. Perhaps she chose to follow Yolanda’s footsteps and considered attending college. Or maybe she simply carved her own definition of success.

In turn, I wonder if Yolanda lost all fear to disappoint others on her way to her own fulfillment, whatever that may mean, so that the triumphs she earns reflect her true self.

As unpredictable as their futures seem, what’s not ambiguous is that the exuberant alliance between Mosquita and Mari embodies Guerrero’s much needed artistic rebelliousness.

Their mere image on the screen defies the conventions of an American independent cinema that never intended to put Chicanas from Southeast L.A. centerstage.

Their undefined bond challenges the rigidness of traditional Latino households that remain averse to understanding that love is love, always.

Their academic victories—earned through mutual support—confront an educational system that positions young people like them to fail.

Through all of these instances of narrative dissent, their story disputes any preconceived notions audiences may harbor about who these young women are supposed to be based on where they are from and on incurious depictions of their community in other media.

Make no mistake, Guerrero made a quietly revolutionary work, most just hadn’t noticed.

“Mosquita y Mari” is currently streaming on Hulu.